Most entrepreneurs recognise financial stress when it hits the bank account. Fewer recognise it when it shows up as fatigue, chronic pain, or a lingering sense that work takes more effort than it used to. Yet the latest figures from Statistics Netherlands tell a story that many small business owners will recognise instantly, even if they have never seen it written down.

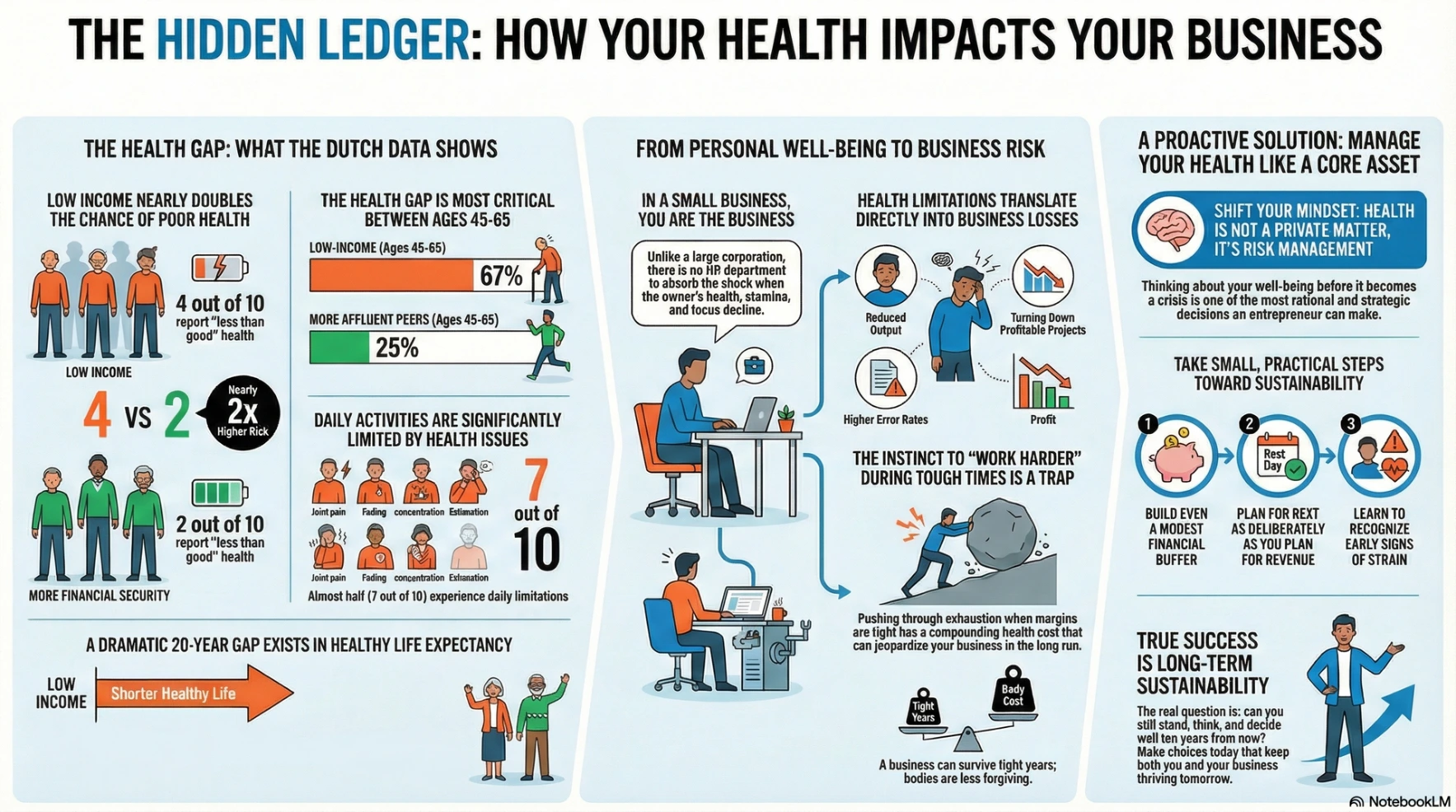

According to the CBS publication Living in Poverty 2025, people living below or just above the poverty line are almost twice as likely to describe their health as poor compared to those with more financial room. Four out of ten say their health is less than good. Among people with more money to spend, that figure is just over two out of ten. This is not abstract data. It is about how bodies respond when margins are thin and recovery time is scarce.

Consider a self-employed electrician in his early fifties, working alone, with a solid order book but little buffer. He keeps going, postpones medical checks, pushes through back pain, and tells himself he will slow down next year. Statistically, he belongs to the group where two-thirds report poor health. Not because they make bad choices, but because their choices are constrained. When money is tight, health quietly becomes negotiable.

The age group where the difference becomes most visible is between 45 and 65. Among people in low-income households, 67 percent say their health is poor. Among their more affluent peers, it is 25 percent. This gap matters deeply in small businesses, where experience, stamina, and continuity are often carried by one or two people. There is no HR department to absorb the shock when health declines. The business feels it immediately.

Limitations caused by health follow the same pattern. Almost half of people with little money experience daily limitations due to health issues, compared to less than a third among those with more financial space. In the 45 to 65 age group, seven out of ten low-income individuals report having a disability. This does not necessarily mean dramatic illness. It often means joints that no longer cooperate, concentration that fades faster, or energy that runs out earlier in the day. In a micro-enterprise, these limits translate directly into reduced output, higher error rates, or the silent decision to turn down work that feels just a bit too demanding.

The long-term picture is even starker. Men with little money live on average nine years less than men with more to spend. For women, the difference is seven years. Even more telling is healthy life expectancy. Men who are not poor live on average more than twenty years longer in good health than men with low incomes. For women, the gap is almost identical. This is not about lifestyle lectures. It is about cumulative pressure. Years of financial uncertainty leave marks that no annual report captures.

For small business owners, the lesson is not moral, nor political. It is practical. Health is not a private matter that sits outside the business. It is one of its core assets. When margins shrink, the instinct is often to work harder and longer. The data suggests this instinct has a cost that compounds over time. Small adjustments matter more than grand solutions. Building even a modest buffer, planning rest as deliberately as planning revenue, and recognising early signs of strain are not luxuries. They are risk management, in the most literal sense.

The CBS figures do not accuse, and they do not dramatise. They simply show what happens when financial pressure becomes a permanent condition rather than a temporary phase. For entrepreneurs, the message is quietly sobering. A business can survive tight years. Bodies are less forgiving. Thinking clearly about health, before it becomes a crisis, is not weakness. It is one of the most rational decisions a small business owner can make.

In the end, sustainability is not only about turnover or growth. It is about whether the person behind the business can still stand, think, and decide well ten years from now. The numbers invite us to look at that future calmly, without fear, and to make small, realistic choices today that keep both the business and the person running it alive and well.

Paolo Maria Pavan

Head of GRC | Market Analyst

Paolo Maria Pavan is a Governance, Risk & Compliance strategist and market analyst known for turning complexity into operational clarity. He works with freelancers, founders, and established SMEs, helping them translate governance discipline, market intelligence, and economic signals into structured execution and defensible growth.